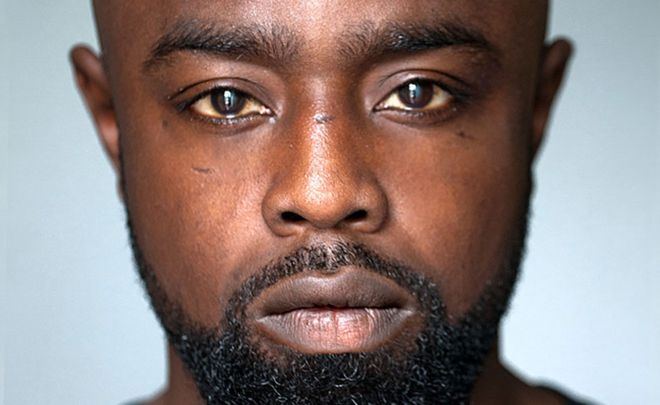

He spent his early life in and out of jail - then Michael Balogun decided he wanted to study to become an actor at one of the world's most prestigious drama schools. Could this seemingly impossible ambition be the catalyst he needed to turn his life around?

As he sat alone in his prison cell, thinking about all the chances he'd messed up, Michael Balogun made a decision: if he couldn't work out what to do with his life that night, he would hang himself.

Balogun closed his eyes and began remembering scenes from his life. The father who abandoned the family. The mother who was sent to prison for dealing drugs. The day he was taken into care and his first forays into street crime. His own jail sentences. The opportunities to go straight he had squandered.

And then a thought flashed into his mind. Acting... He could try acting.

To anyone who had never met Balogun, it would have seemed a wildly incongruous ambition. But it's one he eventually realised. Last year he graduated from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (Rada), one of the world's most prestigious drama schools.

And when he took his place on stage for the first time at the National Theatre's new production of Macbeth alongside such celebrated actors as Rory Kinnear and Anne-Marie Duff, he marvelled at how far he had come. "I would never have imagined myself here," he thought to himself.

Balogun grew up in Kennington, south London, in an unusual home. "My dad wasn't around, my mum was going on holiday a lot, travelling a lot, and it was me and my sisters in the house, alone," he says. There were always people coming in and out. One of his early memories was watching his mother argue with two men. As they left, Balogun saw one of them put a gun in his waistband.

The most traumatic period of his childhood began when he was aged about seven or eight, with his mother's arrest. "No-one can look after a child better than their own mother," he says. "It was like the end of the world for me."

She was sentenced to 15 years in prison, but somehow the authorities didn't realise that Michael and his two sisters had been left alone in the house to fend for themselves. The three of them were used to it, he says. His older sister took care of the housework and sorting out the family's benefits. "We kind of just kept it how it was whenever mum went on holiday."

One day, a year or two later, Balogun fell ill at school. "I remember the teachers saying, 'Oh, we're going to call your mum,' and I remember being like, 'Nah, nah, don't worry, it's fine.'" Eventually they worked out his mother was in prison. Social services were alerted. Balogun and his sisters were taken into care and then went to live with an aunt.

After this, he started to go off the rails.

His criminal career began in Sainsbury's, where he went to steal doughnuts - "I didn't really have much money and I just needed to eat sometimes," he says. By the time he started secondary school, he'd fallen in with a crowd of other south London teenagers with difficult backgrounds.

"I started off stealing, then I started robbing people on the street - handbags and all that stuff. Mugging people." From there he progressed to selling cannabis at school, and by the time he was 16 or 17 he was dealing heroin and crack cocaine on the streets of Kentish Town, north London and Portsmouth.

When he received his first prison sentence - three-and-a half years for possession of heroin with intent to supply - jail felt like a rite of passage. But he still found the experience deeply traumatic.

"That first night, when the door closes behind you and you realise that you're just in a room, you're going to be here until you finish your sentence - that's when reality kicks in." Prison was "a university for crime". He was jailed again soon after his release.

After he was freed a second time, Balogun decided to try going straight. He applied for a job with a High Street bank and, at his interview, he boasted that he was a great salesman who could sell any product - not mentioning, of course, where he'd acquired his sales experience.

Impressed by his confidence, the panel offered him a job. He worked on a cashier's till selling mortgages and packaged accounts. And, true to his word, he was good at it. "This was before the credit crunch where if you went into a bank, they'd offer you all this stuff," he says. Thanks to Balogun's efforts, the branch shot up the company's sales league table. "I was succeeding. I was making that branch where I was working the number one branch in that area."

His aptitude didn't go unnoticed and he was offered a promotion at another branch. Then, one day, Michael was taken aside. "They called me in: 'What were you doing between this time and this time?' Those were the times I'd been in prison. They'd found out." Balogun had never admitted to his employers that he'd served time in jail. He was dismissed.

His sacking shattered his confidence in his ability to hold down a "straight" job. "I just decided to do what I knew best, which was selling drugs, and crime."

Soon after, he was in a nightclub with a group of friends when he got into an altercation with another group. "Some guy pulled out a gun, and because I had a gun on me it all got a bit hectic and it ended up being a shootout. I ended up trying to shoot someone."

Today, at the age of 34, Balogun says he can't believe he could do such a thing.

"Obviously at the time I knew what I was doing was wrong," he says.

"But I always justified it because I was like, 'This is the life I've lived. This is the background I've come from. This is what we do.'

"But looking back now I realise that what I did was stupid and reckless and disgusting. It's a big regret."

Balogun was caught and sentenced to nine years in prison for his part in the incident.

Back inside, at HMP Blantyre House, Kent, Balogun resolved to turn his life around. He decided he wanted to be a chef - "I used to watch Gordon Ramsay's Kitchen Nightmares religiously every week" - and a friendly prison officer suggested he apply for a training place at The Clink, a charity-run restaurant inside HMP High Down, Surrey (it now operates three more restaurants at prisons around England and Wales).

Balogun earned a catering NVQ there, and became eligible for day-release work towards the end of his sentence. He was told a job had been found for him in a place he'd never heard of before - at Rada, in the drama school's canteen. Balogun was delighted - this would be a chance to hone his skills and earn some money. Plus, "I thought there's probably going to be some attractive women floating around, if I'm honest," he says. "Obviously, having been in prison a few years, you know?"

He was nervous when he arrived at Rada, and his time there didn't go well at first. Balogun was told that his vegetable-chopping was too slow and he was relegated to serving drinks at the bar. "I was a bit moody because I was like, 'I didn't come her to work on a bar, I came here to learn to cook,'" he says. "I wanted to be a chef and had all these ideas and ambitions about opening up a restaurant."

Then one day the manager asked if he wanted to watch one of the plays performed by Rada's students. Balogun, who had never been inside a theatre except on a trip to watch Starlight Express when he was at primary school, jumped at the opportunity.

He was ushered into the auditorium. The play was Measure For Measure. "Whenever I thought of Shakespeare, I just thought of, like… these guys running around in old clothes," he says. But this was a modern-dress staging, set in present-day America. "I was like: 'Oh, they're doing New York accents and it's set in New York and people are acting quite contemporary and normal.'"

Another revelation was a production of Mercury Fur, Philip Ridley's controversial play about a post-apocalyptic London. Balogun was mesmerised. "It's one of those things where you watch a play and you forget about life. You are just there and inside this thing, watching everything happen, and it just takes you."

When he went back to prison that night, Balogun raved about what he'd seen. He took his friend and fellow inmate Marvin through the plot, acting out scenes and impersonating the characters.

What struck Marvin, however, was the vivid manner in which Balogun had recounted the play. Marvin told him: "I reckon you could be an actor, you know, bruv. Because you're very dramatic, the way you tell stories. You get into it, you lose yourself."

Balogun wasn't convinced. Surely being an actor wasn't for the likes of him?

He pushed all this to the back of his mind. And anyway, Balogun was about to squander his chances for redemption again.

Taking a mobile phone into prison was strictly forbidden. But, says Balogun, "I was being a bit greedy and I wanted to talk to a couple of friends." As he returned from Rada one day he tried to sneak a phone into his locker. A prison officer spotted it and, straight away, all his privileges were revoked.

No more day release, no more Rada. No more open prison, category-D status - instead, a transfer to closed conditions at HMP Elmley, Kent.

"I think there's something in me, this self-destruction," he says. "This has happened to me a lot in my life. Messing things up, constantly."

To cope with the culture shock of returning to a closed prison, Balogun was smoking the synthetic cannabinoid, Spice. "It messes up your head a lot," he says. "I was having psychotic episodes."

It was at this low ebb that Balogun gave himself a night to decide how to make something of his life, or kill himself. As he closed his eyes and went over memories in his head, he suddenly made the connections between what those around him had been saying.

Marvin, his former fellow inmate, wasn't the first person who had suggested he might have an aptitude for the stage. He'd befriended some of the drama students, some of whom had asked him to practise their lines with them, and one had suggested he was good enough to do it professionally. At school, he recalled, his teachers told him he was a natural performer. Before he'd been exposed as an ex-convict, his superiors at the bank had praised his energy and charisma.

It all made sense to him now - acting was his best chance of redemption. "As soon as that thought came in my head, I just felt like something had been lifted off," he says. "And I knew - instinctively, inside of me - knew that was the right thing to do."

The next day, a psychologist came to see him in his cell about his psychosis. "I'm fine now," he said to her. He told her about his plans to become an actor - and, by coincidence, it turned out the psychologist was a part-time drama teacher. She began bringing him plays each week to read - Noel Coward, Shakespeare. He didn't understand King Lear the first time he read it, but he was determined to learn.

And as he started to make sense of what he was reading, he felt validated - that he could really do this. And what better place to do it than Rada? He was still in contact with students there, who told him how tough it was to get in. Each year 5,000 would apply and only 28 would be admitted.

After his release, his determination to get into Rada hadn't diminished. But even in the unlikely event that he got in, how could he raise the £28,000 course fees? He'd never heard of student loans. He thought: "I'll go back to what I know best - which is drug-dealing - for a bit, save up some money."

So he was selling drugs again - except this time, alongside his illicit business activities, Balogun was taking Shakespeare classes run by a homeless charity. But once again, the police caught up with him, and he ended up back in prison. It was the final wake-up call he needed that he had to quit crime for good.

Six months later, Balogun was released again, and he began applying straight away to drama schools.

For his Rada audition, Balogun chose the St Crispin's Day speech from Henry V. "When he was younger, he was a bit of a rogue. And then he has to become king, so he has to step up to the plate. This is an emotional, rousing speech. I remember reading it and thinking, 'I can do this one.'"

He performed it as though he was talking to his mates in prison.

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

Sometime after the audition, his phone rang. A withheld number. Rada calling to let him know how he'd done.

His heart began beating faster. "We'd like to offer you a place on the BA in acting," a voice down the line told him.

He lay on the floor of his mum's kitchen and cried

This month, as he walked out in front of an audience at National Theatre for the first time, and saw Duff and Kinnear on stage alongside him, Balogun thought about the epiphany in the prison cell that brought him there.

"Obviously circumstances do affect you, and events that happen in your life - but there comes a time in life where you need to take responsibility," he says.

"I strongly believe that your imagination is powerful, and that's where the magic is. If you have an idea, a motivation to do something - just do it, because you'll be surprised what you can do."

Source: BBC

If you can think it, You can do it... Never stop believing in yourself

ReplyDelete